Mexico is where two worlds have fused together to produce a version of Spanish that is far richer in culture than that of its European birthplace. This richness of the Mexican culture should, to a great extent, explain our bias toward their flavor of the Spanish language. A language this rich in cultural heritage often grows into an interesting stewpot of local refranes (sayings) and proverbs unique to its people. It is said, Mexicans are loaded with a saying for virtually any situation in life, which is what makes them such excellent communicators! The sentence being deconstructed in this article demonstrates just that.

These pearls of wisdom are not only meant to liven up your speech or make life more philosophical for you, they also add a new dimension to learning Spanish by offering you some priceless insight into the cultures and lifestyles of the native speakers! These sayings are laden with some of the most local aspects of the Mexican vocabulary and often hint at some really deeply-rooted facets of Mexico’s pre-Columbian cultures. These features make them excellent subjects for our deconstruction activities and accelerated learning. Here’s our subject for today:

Ponte los huaraches antes de meterte en la huizachera. (Put on the sandals before you enter the thorn-field.)

What the little saying above intends to advise is that you should always take all necessary precautions before you embark on any tricky journey or start a difficult task.

As always, we will attempt to assimilate the Spanish in this sentence by breaking it down into small edibel morsels and then putting those pieces back together in order; more like reverse engineering. Let’s start:

Ponte – The Spanish verb, poner means “to put” in English. The same verb, when used as a reflexive (ponerse) takes on the sense of “putting oneself” or “putting on”. This reflexive verb, when conjugated for the familiar subject (tú), becomes ponte. Note the suffix signifying it’s association with tú. A more formal conjugation would be póngale which, obviously, takes usted as its subject. The little accent mark on póngale is just to ensure you pronounce it exactly the way it’s meant to be: With a stress on “o”. Note again, the -le ending that signifies it’s association with usted as against tú. Coming back to our ponte, the word in this context stands for “putting on” as in “wearing something”.

los huaraches – This word comes from the P’urhépecha word, kwarachi, which directly translates into English as “sandal”. This pre-Columbian footwear is made from traditionally hand-woven leather and is a well-known icon of Mexico’s cultural heritage.

Huaraches began to gain popularity in the United States in the 1950s and became known all over North and South America by the turn of this century. If you have ever had the chance to watch Ask The Dust, a Hollywood film set in the Los Angeles of the 1930s starring Salma Hayek and Colin Farrell, you would instantly recognize the rustic sandals worn by Hayek. Hayek is shown to be visibly annoyed when Farrell, perhaps mockingly, mispronounces the word. Most Mexicans would readily concur if you said that few things are more Mexican than a pair of leather huaraches. Want to buy yourself a pair? Head straight for one of those huaracheríos scattered throughout the Mexican countryside.

antes de – This one is easy; simply put, antes de translates into English as “before”. Why de, you ask? We don’t know. These are idiomatic phrases and it’s best to learn them as is without much logic. The antes can, however, be explained; it comes from the Latin word for “before”. The same Latin word has come to form the root of many English words today lending a sense of “before” or “pre”, such as “antebellum” (before the war).

meterte – Meter is a Spanish verb that means “to put in” or “to insert” in English. Used as a reflexive, it means “to put oneself into” or “to enter”. Despite the subtle differences, the context is usually enough to tell which meaning holds. Here, meterte means “you enter”; note the te ending.

en – This one is a simple preposition which most often translates into English as “in”. In this context it gives a sense of “in” though while translating this sentence, this “in” is just implied and omitted in English.

la huizachera – Huizache is a very thorny legume found all over Mexico, El Salvador, Colombia, and Venezuela. It is regarded as a highly invasive weedy species threatening pastures whose pods are sold in local Mexican markets. The name derives from the Nahuatl word, huitztli (thorn). A huizachera is a field full of this plant.

Now let’s bring these small pieces together and see how they lend to the final meaning of the entire sentence. The phrase, Ponte los huaraches means “Put on the huaraches” in the following word-order: Verb (here, familiar imperative of “to put on”) - object (here, “the huaraches”).

The rest of the sentence, antes de meterte en la huizachera translates as “before you enter the huizachera with the following word-order: Preposition1 (here, “before”) - subject (here, omitted but implied to be “you” in the familiar form) - verb (here, “to enter” in the infinitive form) - preposition2 (here, “in” or “into”; not translated into English) - object (here, “the thorn-fields” or “the huizachera”)

Do note here that the reflexive object is often omitted in English; not so in Spanish. Also, such objects are usually suffixed to the verb if it’s in its infinitive form as is the case here (meterte).

These pearls of wisdom are not only meant to liven up your speech or make life more philosophical for you, they also add a new dimension to learning Spanish by offering you some priceless insight into the cultures and lifestyles of the native speakers! These sayings are laden with some of the most local aspects of the Mexican vocabulary and often hint at some really deeply-rooted facets of Mexico’s pre-Columbian cultures. These features make them excellent subjects for our deconstruction activities and accelerated learning. Here’s our subject for today:

Ponte los huaraches antes de meterte en la huizachera. (Put on the sandals before you enter the thorn-field.)

What the little saying above intends to advise is that you should always take all necessary precautions before you embark on any tricky journey or start a difficult task.

The nuts and bolts

As always, we will attempt to assimilate the Spanish in this sentence by breaking it down into small edibel morsels and then putting those pieces back together in order; more like reverse engineering. Let’s start:

Ponte – The Spanish verb, poner means “to put” in English. The same verb, when used as a reflexive (ponerse) takes on the sense of “putting oneself” or “putting on”. This reflexive verb, when conjugated for the familiar subject (tú), becomes ponte. Note the suffix signifying it’s association with tú. A more formal conjugation would be póngale which, obviously, takes usted as its subject. The little accent mark on póngale is just to ensure you pronounce it exactly the way it’s meant to be: With a stress on “o”. Note again, the -le ending that signifies it’s association with usted as against tú. Coming back to our ponte, the word in this context stands for “putting on” as in “wearing something”.

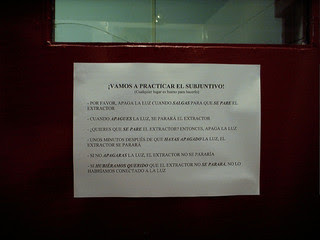

|

| A breeze-friendly huarache Photo credit: Wicker Paradise licensed CC BY 2.0 |

Huaraches began to gain popularity in the United States in the 1950s and became known all over North and South America by the turn of this century. If you have ever had the chance to watch Ask The Dust, a Hollywood film set in the Los Angeles of the 1930s starring Salma Hayek and Colin Farrell, you would instantly recognize the rustic sandals worn by Hayek. Hayek is shown to be visibly annoyed when Farrell, perhaps mockingly, mispronounces the word. Most Mexicans would readily concur if you said that few things are more Mexican than a pair of leather huaraches. Want to buy yourself a pair? Head straight for one of those huaracheríos scattered throughout the Mexican countryside.

antes de – This one is easy; simply put, antes de translates into English as “before”. Why de, you ask? We don’t know. These are idiomatic phrases and it’s best to learn them as is without much logic. The antes can, however, be explained; it comes from the Latin word for “before”. The same Latin word has come to form the root of many English words today lending a sense of “before” or “pre”, such as “antebellum” (before the war).

meterte – Meter is a Spanish verb that means “to put in” or “to insert” in English. Used as a reflexive, it means “to put oneself into” or “to enter”. Despite the subtle differences, the context is usually enough to tell which meaning holds. Here, meterte means “you enter”; note the te ending.

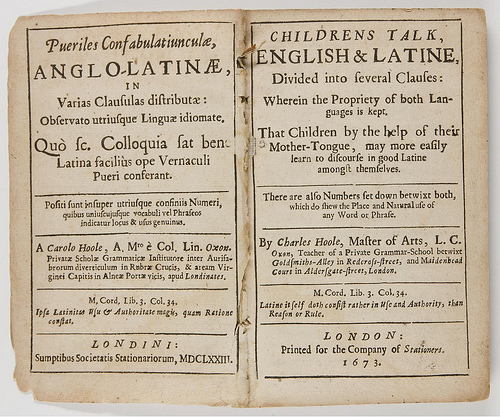

|

| A thorn-filled huizachera Photo credit: Adapting to Scarcity licensed CC BY-SA 2.0 |

la huizachera – Huizache is a very thorny legume found all over Mexico, El Salvador, Colombia, and Venezuela. It is regarded as a highly invasive weedy species threatening pastures whose pods are sold in local Mexican markets. The name derives from the Nahuatl word, huitztli (thorn). A huizachera is a field full of this plant.

String’em together

Now let’s bring these small pieces together and see how they lend to the final meaning of the entire sentence. The phrase, Ponte los huaraches means “Put on the huaraches” in the following word-order: Verb (here, familiar imperative of “to put on”) - object (here, “the huaraches”).

The rest of the sentence, antes de meterte en la huizachera translates as “before you enter the huizachera with the following word-order: Preposition1 (here, “before”) - subject (here, omitted but implied to be “you” in the familiar form) - verb (here, “to enter” in the infinitive form) - preposition2 (here, “in” or “into”; not translated into English) - object (here, “the thorn-fields” or “the huizachera”)

Do note here that the reflexive object is often omitted in English; not so in Spanish. Also, such objects are usually suffixed to the verb if it’s in its infinitive form as is the case here (meterte).